The Bankman-Fried Explanation of Working Hardly, and How Hard is It to Deal With? An Analysis Using a Case Study Against Cohen and Tuchmann

We learned Bankman-Fried was working very hard, 12 hours a day, which seemed low: Bankman-Fried had previously testified he worked as many as 22 hours a day. There was little testimony about what he was up to for the majority of that time. Similarly, I heard a lot about a data protection policy the defense could not produce.

Bankman- Fried had a high-risk play on which to take the stand. Although it gave him the chance to relay his own version of events, it exposed him to questioning by the prosecution. If he were to perjure himself and later be convicted, he risked a harsher sentence too. Paul Tuchmann, a former prosecutor and partner at Wiggin and Dana, testified as the only possible option to mount the “good faith” defense. “It’s very hard to make that defense without calling the client to the stand,” he says, when “the people closest to him testified the opposite.”

Cohen introduced things that seemed to be boring, even though they were meant to confuse the jury. I saw a lot of jurors look at the clock in the back of the courtroom when I was talking about Alameda’s net asset value. The same went for discussion of FTX’s risk engines.

We still have to hear the prosecution’s rebuttal to Cohen’s arguments, such as they were, before the case goes to the jury. But I think even the most talented defense lawyer would struggle with this case. The documentary evidence for the prosecution is so overwhelming, and there are so few pieces of evidence to support Bankman-Fried’s story that Yedidia has not been charged with anything. Bankman-Fried, the last person the jury heard speak, was an avid liar, and we did establish that at length.

Though he was charged with old-fashioned fraud, Bankman-Fried was crypto royalty, which lends his conviction a symbolic importance, says Estes. She says the DoJ has shown that fraud and wheeling-and-dealing is not to be accepted in the industry. An investigation into the CEO of the world largest coin exchange, Changpeng Zhao, is currently ongoing.

After the first hour, the closing statement could have ended. The evidence that Bankman-Fried was involved — from his Google Meet with the other alleged co-conspirators, to the metadata linking him to various incriminating spreadsheets, to the funds traced to entities he controlled — would have been enough. We got a few more hours, as though Roos had rented a backhoe to use for the pile of evidence, and was just going to use it.

As Roos spoke, the jury was focused very closely on him. No one appeared to be napping. People were taking notes while I didn’t see anyone looking at the clock. When the screens that showed the evidence in the middle row malfunctioned, the closing argument went smoothly. The jury listened as Roos spoke directly to them.

Watching Roos, I came to understand why the defense had been jumping around in time so much. Chronological order was bad for Bankman-Fried: it showed pretty clearly that he was learning things and lying about them. The “Assets are fine” tweet, sent November 11th, was four hours after a Signal chat where Bankman-Fried acknowledged an $8 billion difference between what he owed customers and what FTX could pay.

Cohen stated that mistakes aren’t illegal. And he sought to present Alameda and FTX as legitimate, innovative businesses. It was difficult to understand how they were reinventing themselves but never mind. It is certainly true that at its peak, FTX’s valuation was very high.

Tuchmann said that Bankman-Fried’s lawyers would be pleased with his performance. He says that the goal was to present an alternative narrative of events to give Bankman- Fried the opportunity to appeal to the sympathies of the jury.

Bankman-Fried spent the months ahead of his trial antagonizing prosecutors and the court. Originally placed under house arrest, he was sent to jail in August for violations of his bail conditions, including using a VPN to watch a football game and leaking the diary entries of his ex-girlfriend — former Alameda Research CEO Caroline Ellison, who pleaded guilty to federal charges and testified against him in trial — to The New York Times.

In a courtroom that was frequently packed, prosecutors detailed how Bankman-Fried and some of his top lieutenants secretly funneled billions of dollars in customer assets from FTX to Alameda Research, a private trading firm he also controlled.

The U.S. government said the former billionaire treated Alameda like a personal piggybank, using FTX customer money to buy luxury real estate for friends and family, and to make political donations and risky investments.

“This was a pyramid of deceit built by the defendant on a foundation of lies and false promises, all to get money,” Asst. The prosecutor told the court in his closing argument. “And eventually it collapsed, leaving countless victims in its wake.”

It’s a sharp reversal of fortune for a young man who just a year ago was living in a$35 million apartment with some of his co-workers as he ran a business that was estimated to be worth tens of billions of dollars.

The “Mistakes of A.J. Bankman-Fried“, a Charged, Unrependent Executive, Apologized for his “Negative Action”

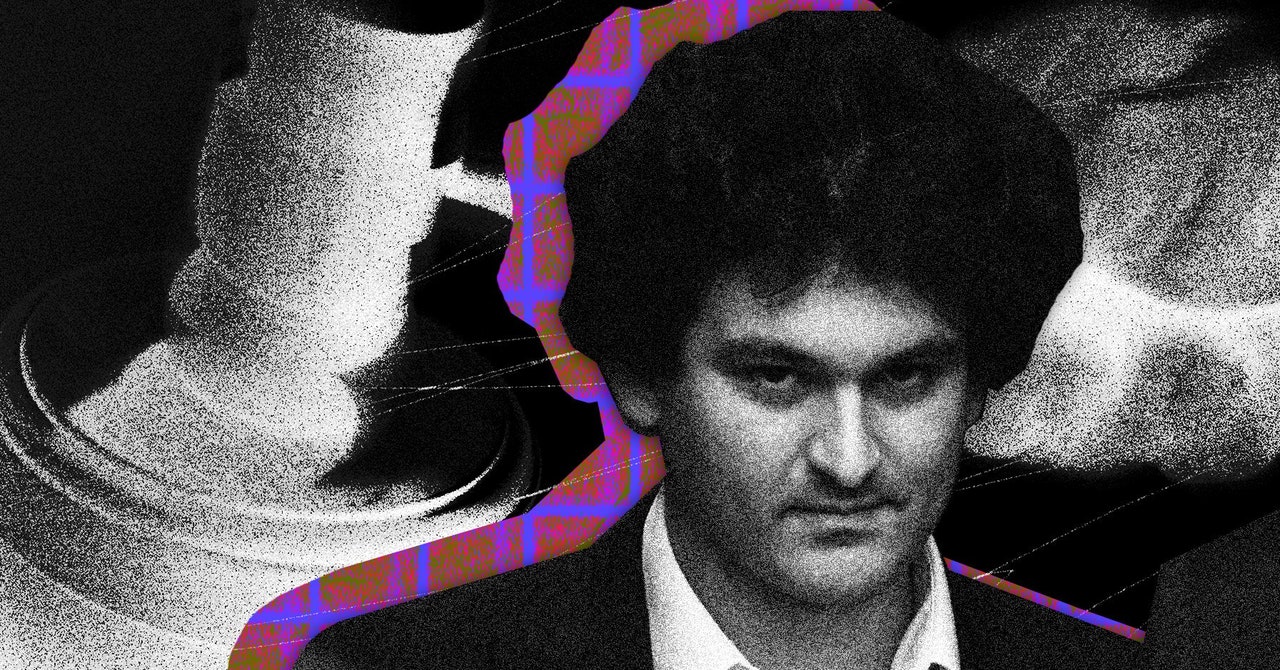

Instantly recognizable by his disheveled hair and his typical attire of a T-shirt and shorts, he was feted at conventions, and hung out with celebrities like former quarterback Tom Brady.

One by one, Bankman-Fried’s former executives started to oppose him, including his previous mistress, who headed Alameda at one point.

She and others pleaded guilty and agreed to co-operation with the federal prosecutors.

They told the court Bankman-Fried directed them to commit crimes, and their comments were especially compelling because the cooperating witnesses weren’t just Bankman-Fried’s colleagues, they were also some of his closest friends.

Bankman-Fried wilted under withering cross-examination from Danielle Sassoon, a formidable prosecutor who clerked for the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

Sassoon used Bankman-Fried’s comments to show that there was a stark difference between what Bankman-Fried said in public, and how he acted behind the scenes.

For example, when FTX was teetering on the brink, Bankman-Fried told his hundreds of thousands of followers on X, formerly known as Twitter, it was in sound shape, even as prosecutors claimed he knew that couldn’t have been farther from the truth.

The picture painted by the prosecution of Bankman-Fried as a villain was at odds with what he had said in his defense.

The defense tried to say that Bankman- Fried was an inexperienced executive who was unable to properly supervise executives at the companies or keep tabs on what was happening.

Mark Cohen, Bankman-Fried’s lawyer, argued in his closing argument that Bankman-Fried made mistakes, and never intended to do anything, but acted in good faith.

Cohen said people make mistakes in the real world. They are a bit hesitant. They aren’t prepared for the unexpected. They make good and bad business decisions, and they make mistakes that later on they wish they could have fixed.”

Bankman-Fried’s conviction as a landmark conviction in US criminal use of cryptocurrency: a case study with a new target: the DoJ

The US Department of Justice (DoJ), says Estes, will consider Bankman-Fried’s conviction a “signature victory,” as its first high-profile crypto scalp. Cryptocurrency has been used for more than a decade to conceal payment for illicit products, enable extortion-based cyberattacks and launder the proceeds of criminal activity. The DoJ will create a specialized team to tackle complex investigations and prosecutions of criminal uses of virtual currency. Until now, the agency had only secured few landmark convictions.